Peace, Love and (Glyphosate in Your) Ice Cream

Tests in the UK and parts of Europe have found traces of glyphosate in several popular Ben and Jerry’s ice cream flavours.

The results come ahead of Wednesday’s hearing in the European Parliament which will be examining allegations that Monsanto unduly influenced regulatory studies into the safety of glyphosate, a key ingredient in its best-selling Roundup weedkiller.

The European ice cream samples were purchased from shops in the Netherlands, France, Germany and the UK after testing earlier this year in the US revealed tainted samples there.

Beyond GM worked with organisers the Organic Consumers Association (OCA) to supply the UK samples, which were bought from major supermarkets in London and shipped to the US for analysis.

Where did the glyphosate come from?

On the one hand, the levels found in 13 of the 14 tested EU samples were low, as were those in the US. On the other hand they were comparable to those which have been shown to cause liver damage in experimental animals over the longer-term.

Differing levels were found too; one of the German samples had no glyphosate, while the three UK samples had the highest detected levels.

A call to Ben & Jerry’s customer service team, as well as information from the company’s various websites says that all the milk for Ben & Jerry’s European operation comes from one farmer owned co-operative in the Netherlands. It is then processed into ice cream at a central plant in Hellendoorn, the Netherlands.

Glyphosate does not readily accumulate in milk and what little testing that has been done in the EU has not found residues in the milk supply.

The most likely explanation is that the residues come from the added ingredients such as cookie dough, fudge brownie and cookie pieces derived from cereal crops often sprayed with glyphosate. Some cross contamination in the transport and storage of these ingredients may also be possible, which could account for varying levels.

That there are any residues at all, however – even in this small number of samples – is troubling to us. It should also be troubling to Ben & Jerry’s.

Not so natural

In July 2017 as reported by the New York Times, testing by the OCA found glyphosate in 10 out of 11 samples of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream.

While the levels of glyphosate were well below the legal limit set by the US Environmental Protection Agency, OCA argued that any presence of the herbicide is potentially dangerous – and misleading.

It called for Ben & Jerry’s to stop labelling its ice creams as “natural” because the cows that supply its milk are fed genetically-engineered maize. In addition, the cereal additives, as well as the oils and sugars in the US are also derived from GM crops and/or from those routinely sprayed with glyphosate-based herbicides.

In Europe dairy cows, including those that supply Ben & Jerry’s milk, are routinely fed on GM soya, and added ingredients like wheat that go into dough, cookies and brownies are, increasingly, routinely sprayed with glyphosate-based herbicide prior to harvest. There is a clear trend for residues to be found in cereals and baked products (as well as other crops such as legumes).

This lead to curiosity about what might be in European samples of the ice cream.

Not just in ice cream

Glyphosate is one of the world’s most widely used broad-spectrum herbicides and accounts for around 25% of the global herbicide market. It is used on farms but also in gardens, on city streets, in parks and playgrounds.

Levels found in the European samples were also within so-called ‘safe’ limits. But these limits do not take into account the hormone-disrupting nature of glyphosate and studies showing that even low levels of endocrine disrupters can be a health risk.

Equally, while most of us don’t eat ice cream every day, glyphosate is being found in other foods we consume daily – as are other harmful pesticides. The contamination in Ben & Jerry’s ice cream adds to this problem.

Foods contaminated with glyphosate residues are a particular problem in the Americas, where Roundup-ready GMO crops have significantly increased the use of glyphosate – and therefore its presence in the food system.

For example, earlier this year, tests conducted by Food Democracy Now and the Detox Project on 29 foods commonly found on US grocery store shelves revealed that many common foods contained levels of glyphosate higher than ‘safe’ limits.

Glyphosate residues were found in General Mills’ Cheerios at 1,125.3 parts per billion (ppb), in Kashi soft-baked oatmeal dark chocolate cookies at 275.57 ppb, and in Ritz Crackers at 270.24 ppb. Kellogg’s Special K cereal, Triscuit Crackers and several other products also had glyphosate residues.

Also last year, testing revealed glyphosate residues in Quaker Oats samples in the US. The company became the focus of a lawsuitwhich alleged that the all-natural claim for the product was misleading given the levels of contamination found. The lawsuit was denied by a federal judge, but the plaintiffs have appealed.

Likewise, recent testing by the US FDA found glyphosate levels in honey that were double the limit allowed in the EU.

In 2016 Canadian researchers found that nearly 30% of food products contained residues of glyphosate.

Europe – a hazy picture

In Europe and the UK testing for glyphosate is inconsistent.

According to the Soil Association, glyphosate use in UK farming has increased by 400% in the last 20 years and residues appear regularly in testing of British cereal and bread products.

Testing has also revealed glyphosate traces in German beer.

A report by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) this year found that nearly all European food products contain pesticide residues. The report was compiled from testing done in individual Member States and included 84,341 samples of produce from conventional agriculture of which 97.2% contained traces of one or more of 774 pesticides.

But only 5329 of these samples – 68% of which were from Germany – were tested for glyphosate which makes it impossible to understand the full level of contamination in the EU.

Glyphosate is also present in European water. A report by The European Glyphosate Environmental Information Sources (EGEIS) looking at surface water monitoring data from 1993-2009 for thirteen European countries found glyphosate in 29% of samples. Residues of glyphosate’s toxic breakdown product (AMPA) were found in 50%.

Water, like food, often contains multiple pesticide residues,

Unsafe at any level?

Regulators have been steadily raising the level of allowable ‘safe’ levels of glyphosate in foods as use of the herbicide, and therefore its presence in the food chain, has become more widespread. The US has the highest ‘safe’ level at 1.7mg per kg of body weight daily. EU levels which were set at 0.3 mg per kg of body weight are due to be raised to 0.5 mg per kg if the controversial bid to relicense glyphosate use in Europe is successful at the end of this year.

In February 2016 a group of international scientists published a consensus statement drawing attention to the risks posed by increasing exposure to glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs). This came after glyphosate’s classification by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a probable human carcinogen.

The scientists noted endocrine (hormone) disrupting effects of glyphosate herbicides in laboratory experiments and called for more studies to clarify whether levels present in foods and the environment can cause such effects in living humans.

This sentiment was echoed by Professor Gilles-Eric Seralini, who was also present at today’s press conference: “Research, both from France and the UK indicates that the levels of glyphosate present in most samples of Ben and Jerry’s ice cream likely pose a health risk. The regulatory levels of glyphosate set in the EU and US are based on outmoded toxicology models that fail to account for the properties of hormone disrupters like glyphosate, which can damage health at even very low levels.”

Europeans want to ‘Stop Glyphosate’

Last month, Prof Ian Boyd chief scientific adviser to the UK’s Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and his colleague Alice Milner, published an opinion in the journal Science which noted the environmental impacts of heavy pesticide use and the lack of regulation:

“The current assumption underlying pesticide regulation – that chemicals that pass a battery of tests in the laboratory or in field trials are environmentally benign when they are used at industrial scales – is false…The effects of dosing whole landscapes with chemicals have been largely ignored by regulatory systems,” the scientists added. “This can and should be changed.”

The scientists added that in the UK “no systematic monitoring of pesticide residues in the environment. There is no consideration of safe pesticide limits at landscape scales.”

What is clear is that Europeans are increasingly aware of pesticides in general, and glyphosate in particular – and that the rising tide of public opinion is against the relicensing of the herbicide due to be decided in December.

This year a coalition of over 100 European NGOs launched the Stop Glyphosate Europe Citizens Initiative (ECI). The goal of an ECI is to get at least 1 million signatures from countries throughout Europe. Having achieved this the European Parliament is legally obliged to respond to Europeans’ demands and consider them in its upcoming decisions. The ECI quickly reached its target.

Caring Dairy?

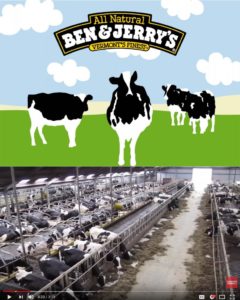

Ben & Jerry’s – unlike many of its competitors – has a well-publicised social mission that supports its image as a socially conscious company.

Its commitment to the Dutch milk collective that supplies its milk is admirable. Its Caring Dairyprogramme, while a long way from organic standards, does have codes of practice on soil health management, animal welfare and health, reduction in antibiotic use and a policy of incentivising outdoor grazing. Its support for climate change initiatives and other worthy causes over the decades is also laudable.

But scratch the surface of the company and you will find a history of challenges and exposes, from both ends of the socio-political spectrum, that suggest the company more than struggles to live up to the comforting narrative.

The company’s milk suppliers in Vermont have been accused of polluting the local waterways. According to Regeneration Vermont, which has been trying to engage with the company for years, Ben & Jerry’s and other Vermont companies have used this idyllic imagery to sell its products, but:

“Gone are the days, however, when most of Vermont’s cows were grazing in spectacularly scenic landscapes. Now, a majority of Vermont’s dairy cows are locked up in what regulators call “confined animal feeding operations” – or CAFOs – with the cows grazing on concrete with a diet rich in GMO corn and pesticide residues… The most striking result of herbicide use during the adoption of GMO corn in Vermont is not increased usage of glyphosate, it is the long-term, almost complete dependence on two highly toxic and water polluting herbicides, atrazine and metolachlor.”

Farmers supplying the milk, according to Regeneration Vermont’s Michael Colby aren’t really seeing much benefit either. ”On average, for each $5-ish pint of Ben & Jerry’s, the dairy farmer who produced its foundational ingredient – milk – gets less than 15 cents from that purchase. And, on average, it costs the farmer about 22 cents to produce that milk.”

Big front, big behind

Peel back the years and other similar stories emerge.

In 2010 Center for Science in the Public Interest, a US non-profit organization providing advice and advocacy toward a healthier food system also urged Ben and Jerry’s to stop using the term ”all natural”. CSPI noted that almost 90% of flavours contained ingredients that had been chemically modified and that calling products with unnatural ingredients “natural” when they’re made in a lab, not a farm, is false and misleading.

In 1999 Ben & Jerry’s label claim that its non-bleached eco-friendly packaging (& thus its ice cream) was free of cancer-causing dioxins was challenged by Citizens for the Integrity of Science – not so much liberal activists as conservative skeptics and defenders against what they see as ‘junk science’, who seemed to be trying to prove that dioxins in the food chain were benign. The tests revealed that a sample of Ben & Jerry’s World’s Best Vanilla ice cream contained 0.79 parts per trillion of dioxin about 190 times greater than the “virtually safe dose” of dioxin determined by the US Environmental Protection Agency.

In the early 1990s the company’s Rainforest Crunch flavour ice cream, which had Brazil nuts in it, claimed that “money from these nuts will help Brazilian forest peoples start a nut-shelling cooperative.” Saving the rainforest was a popular campaign at the time. But the small cooperative found it difficult to keep up with demand and by all accounts collapsed under the weight of it. Investigations showed that Ben & Jerry’s was actually purchasing 95% of the nuts for its Rainforest Crunch from Brazilian agribusinesses and less than 5% from the cooperative.

An alternative ending to this story

As each crack is exposed Ben & Jerry’s simply meets its critics with even more comforting promises of future sustainability. It has the money and the power and the reach to change narratives on a dime in the name of damage control.

And that is what has just happened.

The company’s response to these latest laboratory tests was to quickly turn a Guardian report which was to exclusively reveal the test results into a story of the company’s heroism.

Ahead of a press conference tomorrow at the European Parliament to announce the findings of the EU tests, the Guardian has this evening reported that Ben & Jerry’s will introduce a new organic line next year (in the US) and will aim to be glyphosate-free (it is not clear if this is in the US or worldwide) by 2020.

[Update 13/1/17: The move to organic will only include the dairy base mix for Ben & Jerry’s ice cream and not the cereal ingredients which are the most likely source of the glyphosate].

This is an intriguing development – and one that, it could be be argued, was intended to eclipse the story of the NGOs that exposed the glyphosate contamination in the first place. It remains to be seen whether the proposed timeline can be met and to what extent the new line will make a difference. Ben & Jerry’s anticipate it will only account for 6% of its total US sales.

Where do we go from here?

Take away the funky cartoons and packaging and Ben & Jerry’s is just another large industrial food producer, functioning within an even larger system that is dysfunctional at best and dangerous at worst.

But increasingly frequent reports of food scares – from horsemeat burgers, to hepatitis sausages, to insecticide-containing eggs, to chicken past its sell-by date being repackaged for sale, to the free fruit and vegetables for school kids contaminated with higher levels of pesticides than conventional produce – show just how often that industrial food system gets it wrong.

A move to 100% organic, in many ways, is a next logical step for a company like Ben & Jerry’s. Certainly it makes business sense. Indeed many companies are waking up to the fact that organic is the only food business sector that is experiencing significant and sustained growth.

A move to organic would also ensure that the cows that supply Ben & Jerry’s milk are not fed on GM feed.

But let’s not pretend that such a move is simple. The infrastructure must be there – i.e. there must be enough cows to supply the organic milk, reliable sources for organic flavours and additives, and a dedicated processing plant to ensure no possibility of cross contamination. This will be hard to guarantee in global brand quantities in the US and perhaps even harder in Europe – which is why the aspiration for how little organic will represent to the brand is so small.

The announcement by Ben & Jerry’s is superficially positive, but it didn’t spring out of thin air. It came from a company under pressure on many sides to actually live up to its own hype.

Let’s see what happens next.

Supporting materials:

- EU relevancy statement

- Certificate of analysis – UK

- Certificate of Analysis – France & Netherlands

- Certificate of Analysis – Germany

This article first appeared at Beyond GM